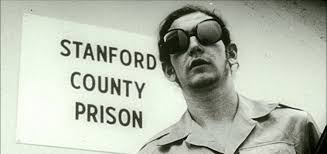

Stanford Prison Experiment

The 1970s, disco, bellbottoms and drugs rolled onto the streets of California and just about everywhere else, but with it the 70s brought something a little more sinister- curiosity.

In 1971, Zimbardo, a highly esteemed psychologist, leaned into his curiosity about prisons, specifically accounts of guard brutality and what causes such accusations. In order to learn the psychology behind power imbalances and how the environment affects behavior, Zimbardo made an artificial jail in empty classrooms of Stanford. Soon after advertisements for volunteers, Zimbardo had 24 of the most “normal,” mentally and physically stable, mature and no history of mental or medical problems, men, all relatively young. They were paid $15 a day. They randomly assigned each participant a duty of “prisoner” or “guard.” After one drop out and two reserves, they ended up with 10 prisoners and 11 guards. And thus began the experiment.

According to Saul McLeod, “Prisoners were… arrested at their homes, without warning, at taken to the police office.” Blindfolded, they were each taken to the makeshift prison where they were stripped of their clothes and names and with that their individuality. They were given smocks to wear, which displayed their number that would take the place of their names. Similarly, the guards were given identical uniforms as well as sunglasses to prevent eye contact with prisoners. From here they took the roles as prisoners and guards. According to McLeod, “Guards were instructed to do whatever they thought was necessary to maintain law and order in the prison and to command the respect of the prisoners. No physical violence was permitted.”

All participants were aware of the situation, as is standard by the APA that all experiments be disclosed to participants, however, they began to take their assigned roles very seriously, very quickly. As some participants would later claim they were intentionally trying to “stir things up,’’ which may have drastically changed the events that followed or just sped them up (The Stanford Prison Experiment Document).

Within the first couple of hours, the roles started to set in. Prisoners talked very little about the “outside world” and would even “snitch” on fellow prisoners to guards. Guards quickly set into harassing the prisoners. They took advantage of counts (lining up all of the prisoners and having them say their numbers), waking them up in the middle of the night to do them over and over. The counts were significant in that they both asserted the authority of the guards while also belittling the prisoners to just their numbers. The guards also made the prisoners do jumping jacks, push-ups, and even clean the toilets with their bare hands.

36 hours into the experiment one of the prisoners, #8612, “began suffering from acute emotional disturbance, disorganized thinking, uncontrollable crying, and rage” (McLeod). He began to yell things including, “Jesus Christ, I’m burning up inside, don’t you know?” After talking to a “prison consultant,” prisoner #8612 was reintroduced to the prison. He began telling other prisoners, “You can’t leave. You can’t quit.” This put all the prisoners on ease and made the experiment feel real. However, prisoner #8612 left after Zimbardo realized the extent of his condition.

On the second day, a surprising rebellion among the prisoners broke out. According to McLeod, “the prisoners removed their stocking caps, ripped off their numbers, and barricaded themselves inside the cells by putting their beds against the door.” The guards used a fire extinguisher to force the prisoners away from the doors, took their beds, and their smocks. Leaders of the rebellion were put in “solitary confinement,” (a hall closet). Due to the rebellion, the prisoners that led the rebellion got their food privileges revoked while others got special food privileges.

The next day, the participant’s parents were scheduled a visit. The guards ordered the prisoners to wash the prison and their cells. After this visit, the rumor of an escape spread, derived from prisoner #8612 who allegedly told a fellow prisoner he would come back and bust him out, which made the guards extra tough on the remaining prisoners. Hearing about the escape plan, Zimbardo sat in the hallway to his prison waiting for anyone to come. Although no one came to bust out the prisoners, a colleague of Zimbardo’s past, questioned Zimbardo to which he became hostile. Zimbardo had truly taken on his role of “prison warden.”

To evaluate the validity of the prison, Zimbardo invited a Catholic priest to talk to the prisoners. Most of the prisoners introduced themselves as their numbers rather than their names. The priest asked the prisoners what steps they were taking to get out of prison, had they talked to their lawyers, etc. While talking to the priest, prisoner #819 began to hysterically cry. They took off his shackles and left him alone to go get him food and a doctor all the while the other prisoners were orders to chant “prisoner #819 did a bad thing” under the room he was in. When the psychologists came back #819 was sobbing and didn’t want to leave because the others thought he was bad. Zimbardo himself had to come in and remind him it was all an experiment and that he could leave whenever he wanted to. #819 stopped crying as if nothing had been wrong.

Originally, the experiment was supposed to go on for two weeks but Zimbardo put an end to it after the 6th day. It was Christina Maslach who recognized the abuse going on and told Zimbardo to shut it down.

Although this whole ordeal was unfortunate it did teach us about how and why people do things. Environment plays a big part in how someone will react to a situation and their overall personality. This is important to think about throughout the day, before you get mad at someone, or before you blame someone for something they cannot control.